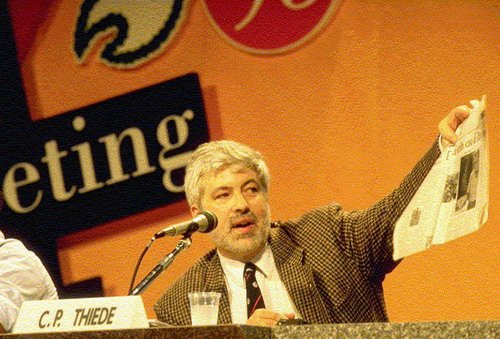

by

Damien F. Mackey

When reading through Anthony Everitt’s 392-page book, Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome (Random House, NY, 2009), I was struck by the constant flow of similarities between Hadrian and Augustus - which the author himself does nothing to hide.

Here are some of them:

Pp. 190-191:

Ten years into his reign, Hadrian announced to the world that, speaking symbolically, he was a reincarnation of Augustus.

P. x:

… Augustus, whom Hadrian greatly admired and emulated.

P. 145:

Flatterers said that [Hadrian’s] eyes were languishing, bright, piercing and full of light”. …. One may suspect that this was exactly what Hadrian liked to hear (just as his revered Augustus prided himself on his clear, bright eyes).

P. 190:

… the true hero among his predecessors was Augustus.

For the image on Hadrian’s signet ring to have been that of the first princeps was an elegantly simple way of acknowledging indebtedness …. Later, he asked the Senate for permission to hang an ornamental shield, preferably of silver, in Augustus’ honor in the Senate.

P. 191:

What was it that Hadrian valued so highly in his predecessor? Not least the conduct of his daily life. Augustus lived with conscious simplicity and so far as he could avoided open displays of his preeminence.

P. 192:

Both Augustus and Hadrian made a point of being civiles principes, polite autocrats.

….

Whenever Augustus was present, he took care to give his entire attention to the gladiatorial displays, animal hunts, and the rest of the bloodthirsty rigmarole. Hadrian followed suit.

P. 193:

Hadrian followed Augustus’ [consulship] example to the letter - that is, once confirmed in place, he abstained.

….

Hadrian’s imitation of Augustus made it clear that he intended to rule in an orderly and law- abiding fashion ... commitment to traditional romanitas, Romanness. It was on these foundations that he would build the achievements of his reign.

Like the first princeps, Hadrian looked back to paradigms of ancient virtue to guide modern governance. Augustus liked to see himself as a new Romulus …. Hadrian followed suit ….

P. 196:

[Juvenal] was granted … a pension and a small but adequate farmstead near Tibur …. Hadrian was, once again, modelling himself on Augustus, who was a generous patron of poets ….

P. 202:

[Hadrian] conceived a plan to visit every province in his wide dominions. Like the first princeps, he liked to see things for himself….

P. 208:

Hadrian introduced [militarily] the highest standards of discipline and kept the soldiers on continual exercises, as if war were imminent. In order to ensure consistency, he followed the example of Augustus (once again) … by publishing a manual of military regulations.

P. 255:

[Eleusis] … at one level [Hadrian] was merely treading in the footsteps of many Roman predecessors, among them Augustus.

P. 271:

… with his tenth anniversary behind him … the emperor judged the time right to accept the title of Pater Patriae, father of his people. Like Augustus, and probably in imitation of him, he had declined the Senate’s offer for a long time ….

P. 277:

[Hadrian] was soon widely known throughout the Hellenic eastern provinces as “Hadrianos Sebastos Olumpius”, Sebastos being the Greek word for Augustus ….

P. 322:

The consecration ceremony was modeled on the obsequies of Augustus.

Part Two:

Here are some more comparisons from the same book:

P. 31:

Augustus’ constitutional arrangements were durable and, with some refinements, were still in place a hundred years later when the young Hadrian was becoming politically aware.

P. 58:

In Augustus’ day, Virgil, the poet laureate of Roman power, had sung of an imperium sine fine. A century later he still pointed the way to an empire without end and without frontiers.

P. 130:

… [Hadrian] depended on friends to advise him. Augustus adopted this model ….

P. 168:

So far as Hadrian was concerned [the Senate] offered him the high title of pater patriae ….

He declined, taking Augustus’ view that this was one honor that had to be earned; he would defer acceptance until he had some real achievements to his credit.

P. 173:

So military and financial reality argued against further enlargement of the empire. … Augustus, who had been an out and out expansionist for most of his career ….

… the aged Augustus produced a list of the empire’s military resources very near the end of his life. …. Hadrian may well have seen a copy of, even read, the historian’s [Tacitus’] masterpiece.

P. 188:

… all the relevant tax documents were assembled and publicly burned, to make it clear that this was a decision that could not be revoked. (Hadrian may have got the idea for the incineration from Augustus, for Suetonius records that … he had “burned the records of old debts to the treasury, which were by far the most frequent source of blackmail”).

P. 198:

His aim was to create a visual connection between himself and the first princeps, between the structures that Augustus and Agrippa had left behind them and his own grand edifices …. Beginning with the burned-out Pantheon. ….

Hadrian had in mind something far more ambitious than Agrippa’s temple. …. With studied modesty he intended to retain the inscribed attribution to Agrippa, and nowhere would Hadrian’s name be mentioned.

Mackey’s comment: Hmmmm ….

P. 233:

It can be no accident that the ruler [Hadrian] revered so much, Augustus, took the same line on Parthia as he did - namely, that talking is better than fighting.

P. 324:

As we have seen, until the very end of his reign, Augustus was an uncompromising and bellicose imperialist. Dio’s prescription [“Even today the methods that he then introduced are the soldiers’ law of campaigning”] fits Hadrian much more closely, and he must surely have had this example in mind when penning these words.

Part Three

“This is the chief thing:

Do not be perturbed, for all things are according to the nature of the

universal; and in a little time you will be nobody and

nowhere, like Hadrian and Augustus”.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

The names “Augustus” and “Hadrian” often get linked together.

For instance, for Hadrian - as we read here: “Augustus was an important role model”:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/themes/leaders_and_rulers/hadrian/ruling_an_empire

Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (reigned 27 BC–AD 14), had also suffered severe military setbacks, and took the decision to stop expanding the empire. In Hadrian’s early

reign Augustus was an important role model.

He had a portrait of him on his signet ring and kept a small bronze bust of him among the images of the household gods in his bedroom.

Like Augustus before him, Hadrian began to fix the limits of the territory that Rome could control. He withdrew his army from Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, where a serious insurgency had broken out, and abandoned the newly conquered provinces of Armenia and Assyria, as well as other parts of the empire. ….

Hadrian was even “a new Augustus” and an “Augustus redivivus”.

Thus Anthony R. Birley (Hadrian: The Restless Emperor, p. 147):

Hadrian's presence at Tarraco in the 150th year after the first emperor was given the name Augustus (16 January 27 BC) seems to coincide with an important policy development. The imperial coinage at about this time drastically abbreviates Hadrian's titulature. Instead of being styled 'Imp. Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus’, he would soon be presented simply as 'Hadrianus Augustus'. The message thereby conveyed is plain enough: he wished to be seen as a new Augustus. Such a notion had clearly been in his mind for some time. It cannot be mere chance that caused Suetonius to write in his newly published, Life of the Deified Augustus, that the first emperor had been, ‘far removed from the desire to increase the empire of for glory in war’ — an assertion which his own account appears to contradict in a later passage. Tacitus, by contrast, out of touch – and out of sympathy – with Hadrian from the start, but aware of his aspirations to be regarded as an Augustus redivivus, seems subversively to insinuate, in the Annals, that a closer parallel could be found in Tiberius. ….

“In Hadrian: The Restless Emperor, Anthony Birley, according to a review of his book, “brings together the new ... story of a man who saw himself as a second Augustus and Olympian Zeus”.

Architecture

Hadrian is often presented as a finisher, or a restorer, of Augustan buildings. For example: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=20867&printable

The Pantheon is one of the few monuments to survive from the Hadrianic period, despite others in the vicinity having also been restored by him (SHA, Hadrian 19). What is unusual is that rather than replacing the dedicatory inscription with one which named him, Hadrian kept (or more likely recreated) the Agrippan inscription, reminding the populace of the original dedicator. At first this gives the impression that Hadrian was being modest, as he was not promoting himself. Contrast this with the second inscription on the façade, which commemorates the restoration of the Pantheon by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in 202 CE (CIL 6. 896). However, by reminding people of the Pantheon’s Augustan origins Hadrian was subtly associating himself with the first emperor. This helped him legitimise his position as ruler by suggesting that he was part of the natural succession of (deified) emperors. It is worth noting that Domitian had restored the Pantheon following a fire in 80 CE (Dio Cassius 66.24.2), but Hadrian chose to name the original dedicator of the temple, Agrippa, rather than linking himself with an unpopular emperor. In addition, the unique architecture of the Pantheon, with its vast dome, was a more subtle way for Hadrian to leave his signature on the building than an inscription might have been – and it would have been more easily ‘read’ by a largely illiterate population.

Thomas Pownall (Notices and Descriptions of Antiquities of the Provincia Romana of Gaul),

has Hadrian, “in Vienne”, purportedly repairing Augustan architecture (pp. 38-39):

That the several Trophaeal and other public Edifices, dedicated to the honour of the Generals of the State, were repaired by Augustus himself, or by his order, preserving to each the honour of his respective record of glory, we read in Suetonius …. And it is a fact, that the inhabitants of Vienne raised a Triumphal Arc, to grace his progress and entry into their town. The reasons why I think that this may have been afterward repaired by Hadrian are, first, that he did actually repair and restore most of the Monuments, Temples, public Edifices, and public roads, in the Province: and next that I thought, when I viewed this Arc of Orange, I could distinguish the bas-relieves and other ornaments of the central part of this edifice; I mean particularly the bas-relief of the frieze, and of the attic of the center, were of an inferior and more antiquated taste of design and execution than those of the lateral parts; and that the Corinthian columns and their capitals were not of the simple style of architecture found in the Basilica, or Curia, in Vienne, which was undoubtedly erected in the time of Augustus, but exactly like those of the Maison carrée at Nimes, which was repaired by Hadrian.

La Maison Carrée de Nîmes

Edmund Thomas will go a step further, though, and tell that the Maison carrée belonged, rather, to the time of the emperor Hadrian (Monumentality and the Roman Empire: Architecture in the Antonine Age, p. 50):

Also worth mentioning is the so-called 'Temple of Diana' at Nîmes.

Hadrian is often presented as a finisher, or a restorer, of Augustan buildings. For example: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=20867&printable

The Pantheon is one of the few monuments to survive from the Hadrianic period, despite others in the vicinity having also been restored by him (SHA, Hadrian 19). What is unusual is that rather than replacing the dedicatory inscription with one which named him, Hadrian kept (or more likely recreated) the Agrippan inscription, reminding the populace of the original dedicator. At first this gives the impression that Hadrian was being modest, as he was not promoting himself. Contrast this with the second inscription on the façade, which commemorates the restoration of the Pantheon by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in 202 CE (CIL 6. 896). However, by reminding people of the Pantheon’s Augustan origins Hadrian was subtly associating himself with the first emperor. This helped him legitimise his position as ruler by suggesting that he was part of the natural succession of (deified) emperors. It is worth noting that Domitian had restored the Pantheon following a fire in 80 CE (Dio Cassius 66.24.2), but Hadrian chose to name the original dedicator of the temple, Agrippa, rather than linking himself with an unpopular emperor. In addition, the unique architecture of the Pantheon, with its vast dome, was a more subtle way for Hadrian to leave his signature on the building than an inscription might have been – and it would have been more easily ‘read’ by a largely illiterate population.

Thomas Pownall (Notices and Descriptions of Antiquities of the Provincia Romana of Gaul),

has Hadrian, “in Vienne”, purportedly repairing Augustan architecture (pp. 38-39):

That the several Trophaeal and other public Edifices, dedicated to the honour of the Generals of the State, were repaired by Augustus himself, or by his order, preserving to each the honour of his respective record of glory, we read in Suetonius …. And it is a fact, that the inhabitants of Vienne raised a Triumphal Arc, to grace his progress and entry into their town. The reasons why I think that this may have been afterward repaired by Hadrian are, first, that he did actually repair and restore most of the Monuments, Temples, public Edifices, and public roads, in the Province: and next that I thought, when I viewed this Arc of Orange, I could distinguish the bas-relieves and other ornaments of the central part of this edifice; I mean particularly the bas-relief of the frieze, and of the attic of the center, were of an inferior and more antiquated taste of design and execution than those of the lateral parts; and that the Corinthian columns and their capitals were not of the simple style of architecture found in the Basilica, or Curia, in Vienne, which was undoubtedly erected in the time of Augustus, but exactly like those of the Maison carrée at Nimes, which was repaired by Hadrian.

La Maison Carrée de Nîmes

Edmund Thomas will go a step further, though, and tell that the Maison carrée belonged, rather, to the time of the emperor Hadrian (Monumentality and the Roman Empire: Architecture in the Antonine Age, p. 50):

Also worth mentioning is the so-called 'Temple of Diana' at Nîmes.

It

was roofed with a barrel-vault of stone blocks, unusual for western

architecture, and its interior walls, with engaged columns framing triangular and

segmental pediments … resemble those of the 'Temple of Bacchus' at Baalbek ….

It seems to have formed part of the substantial augusteum complex

built around a substantial spring …. The date of the building is much disputed;

but the resemblance to the architecture of Baalbek and the association of

Antoninus Pius with Nemausus [Nîmes], may be indications of the Antonine date

formerly suggested. …. Indeed, the famous ‘Maison Carrée’ in the same city,

usually

regarded as an Augustan monument, has recently been redated to the same period, when the town was at its height, and may even be the ‘basilica of wonderful construction’ founded by Hadrian around 122 [sic] ‘in honour of Plotina the wife of Trajan’ ….

regarded as an Augustan monument, has recently been redated to the same period, when the town was at its height, and may even be the ‘basilica of wonderful construction’ founded by Hadrian around 122 [sic] ‘in honour of Plotina the wife of Trajan’ ….

The

Maison Carrée is the best preserved Roman temple in the world today and is a

stunning building to visit.